Memorial

These images account for the meeting between Julián and the archive that Yuyachkani theatre group disposes for the public at the entrance of Sin título, técnica mixta |LS|Untitled, mixed media|RS|, a production that questions the construction of Peruvian historical memory. The archive invites us to delve into newspaper clippings, photographs, school books, artistic images and other documents before entering the room where the scenic action takes place. The entire production examines the Guerra del Pacífico (1873-1889) and the Conflicto Armado Interno (1980-2000), two wars that define Peru’s republican era and reveal the history of the country’s fractures.

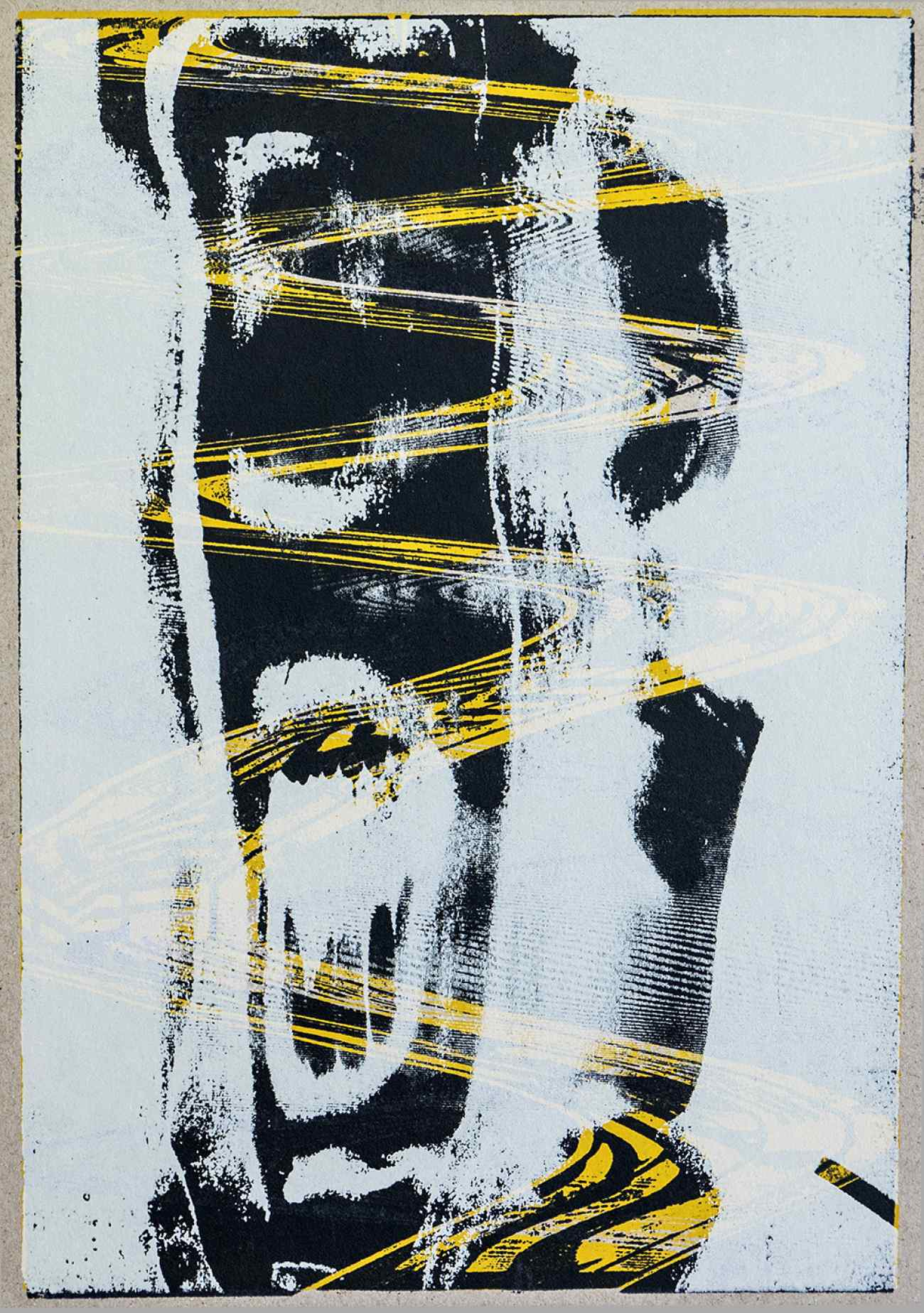

Memorial is a series of photocopies marked by the manual manipulation of each of its documents. Traces, decompositions, creases, slippings, glazings, grain degradation, fragments, inversions, double exposure. Its title leads us directly to the process of establishing certain things -events, characters, symbols- as that which defines our shared history. However, this series inquires about the relation between the images of war and the concrete forms taken by two very different kinds of social abstractions: national symbols and money. The former quickly lose their shape, disfiguring the limits of the mental space in which Peru has been represented throughout its history; the latter makes its entrance about halfway through the series –when Túpac Amaru clashes against the dollar–, soon to saturate the entire space of the paper.

“Money was invented so that people wouldn’t have to look each other in the eyes” (Godard, Film Socialisme), in the same way that national symbols seek to ensure the permanence of the imagined community. In both cases they function through misrecognition. That is, as a way of ensuring that, despite what we see and perceive directly, an ideal space where all contradictions are resolved takes place. The map –which here depicts the representational space where we introduce fictions, rather than the actual geographical reality– and the bills –as a daily replacement for the map that places those same fictions in our hands– teach us how to look away from the decomposition of social bonds caused by both wars. Precisely what is addressed throughout the rest of the series.

Images appear amidst the national myth and its monetary form that define what we should disregard in order to sustain the fiction of a country with no fractures. Many of the documents refer to our most recent war, pointing out that the establishment of official narratives and their imagery, where heroes and villains are defined as such, is a process that marks our present. A dispute that remains unfinished –and probably will never be solved– but that, for many, is not really happening. Despite this, both Fujimori and Abimael appear as two personifications of war, where they are confronted less as a contradiction than as a synthesis. One and the other, after all, aimed to become the face of the nation, to be printed on bills that allow us to avoid each other’s eyes. The problem Memorial faces –much like Yuyachkani’s production– is how to imagine a way out of the symbolic conundrum we find ourselves in. A way out that overcomes those social forms of misrecognition (emblems, money) and comes to terms with the contradictions that we share. Perhaps the only thing we really share.

Mijail Mitrovic

This link contains a PDF with the inside pages of the book. You can download and print at your home, at work or at the copy shop in your neighborhood. If you have the covers you can finish building the book yourself.